In my February 28 newsletter, I shared Chapter Two of my memoir-in-progress, Threads of Life: A Father’s Untold Stories. Today, I’m posting Chapters 5 and 6 of the manuscript.

In this instalment of my memoir, I return to 1965, the year my family first set foot in Montreal. These early chapters trace our tentative steps into a new life: the shock of snow-covered mornings, the sting of isolation at school, and the quiet resilience we forged in the face of rejection and cultural dissonance. It’s the beginning of a long becoming, of identity, belonging, and memory.

Reading (or rereading) my previous post will give you a better grasp of the unfolding story.

Click here for Chapter 2.

Chapter 5

Getting Settled

The very next day, we were greeted by Zio (uncle) Totò and Zio Aldo.

“Dai, Andiamo, c’è una signora qui vicino che si trasloca e vende stufa e frigo,” said one of the uncles. They were taking Dad to see a second-hand fridge and stove.

Zio Mattucio, who owned a grocery store, came by with five boxes of groceries. Zio Gaetano, who owned the only Fiat dealership in Canada, brought a thermos of hot coffee and donuts. He handed my mother a $20 bill as a welcome gift.

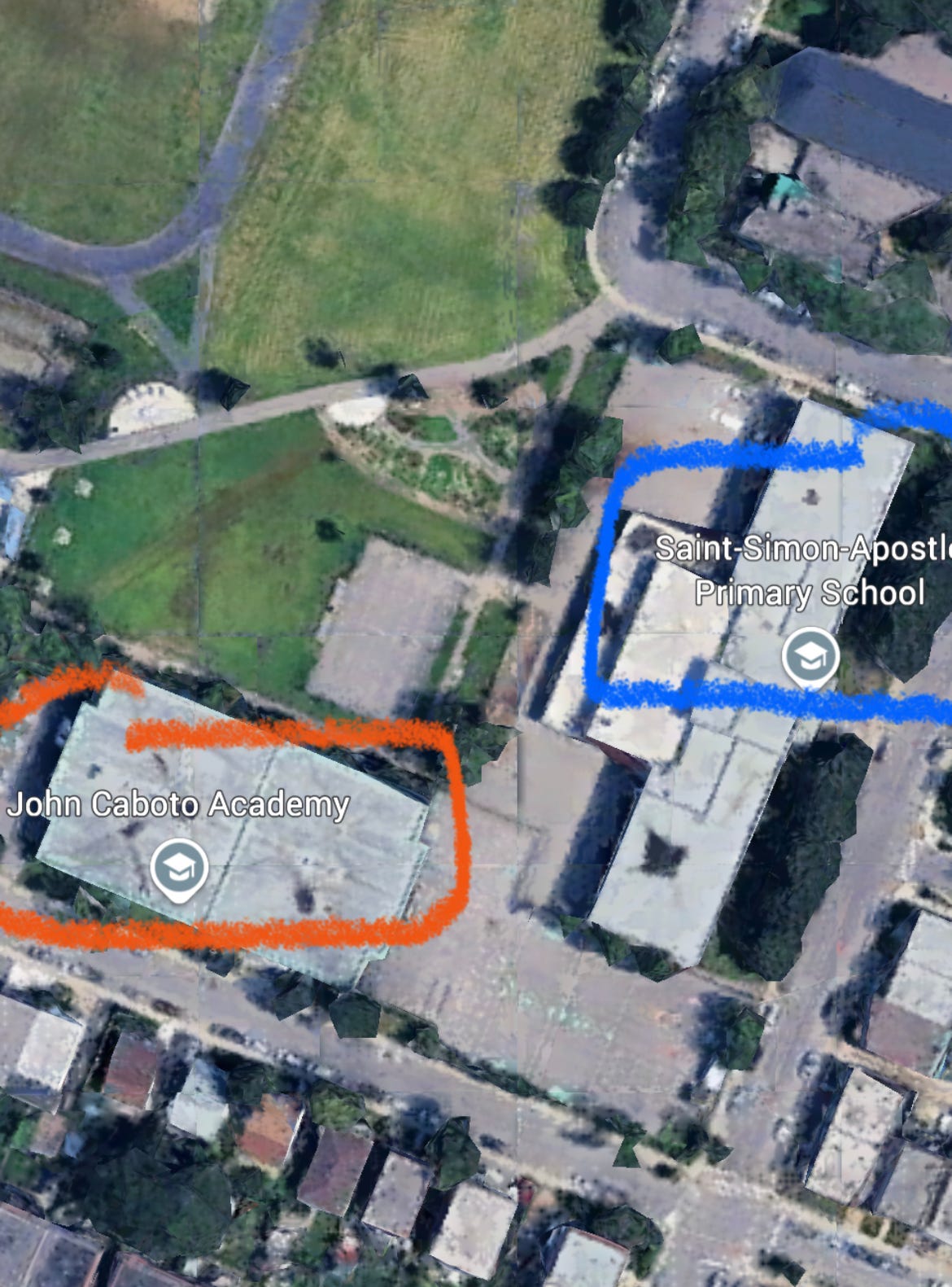

Gino and Pina went out scouting for jobs in nearby factories with our cousin Michele. Geny, who turned 14 that year, was accompanied by our cousin Ada to John Cabot, the local English elementary school. Pompeo, just two years old, stayed home with Mom.

As for me, my Aunt Pippinella took me to Saint-Simon Apôtre, a French school. While I sat in the principal’s office, a tall, distinguished gentleman asked my aunt if I should be enrolled in French or bilingual classes. She replied it would be better for me to learn both languages, important here in the province of Quebec. I didn’t have much say in the matter, and the very next day, I began classes that had already been in session for over a month.

It was customary to be placed a year behind, so I repeated the fourth grade I had just finished back in San Vittore.

Mme Martineau was a short, stubby middle-aged woman who seemed to like me, but I couldn’t understand a word of what she said. At first, I tried to guess whether we were speaking French or English. Then I realized: mornings were French, afternoons were English.

I invented games to ward off boredom. One day, I counted the holes in the ceiling tiles. It wasn’t that hard, 30 holes by 30 in one tile made 900. There were 25 tiles by 28 across the room: 700 tiles. Seven hundred tiles times 900 holes, voilà, 630,000 holes in the classroom ceiling.

Another game involved the spinning Shell gas station sign visible from my classroom window. It turned endlessly. I’d try to look at it precisely when the full sign faced me. I kept score on the back page of my copybook and averaged the results by the end of the day.

But my favorite game was watching raindrops race down the windowpane, guessing which one would reach the bottom first.

I endured the profound boredom by drifting into daydreams of San Vittore, afternoons with Pino and Marco at the piazza, soccer games, and animated evening play. My favorite game was hide and seek. The village offered endless hiding spots: behind the back door of Ginotto’s bar, inside Lilinda’s bocce field entrance, or even the first floor of the clock tower, where I learned to tell time. Hiding always came with a mix of excitement and nervousness, hoping not to be caught before making it back to the piazza fountain.

Chapter 6

Losing Your Identity and Learning to Adapt

There was something different about having Kellogg’s Cornflakes before school, compared to dipping biscotti into a warm café latte back home.

Our household was a bit chaotic. Mom trying to juggle lunches, school schedules, and work routines, while also learning to adapt to our new life.

Back in Italy, she ran the household and the shoe store while Dad traveled to different mercati with his business. Her schedule was always hectic, but in San Vittore, she didn’t need to worry much about where the kids were, the entire village acted as a babysitter.

Mom was a good-hearted woman. I must say, the disciplinarian in our home was Dad.

He had a distinctive whistle, an ascending high C that cut off sharply, like falling off a cliff. We could hear it from nearly every corner of the village. And when we did, we didn’t walk, we ran.

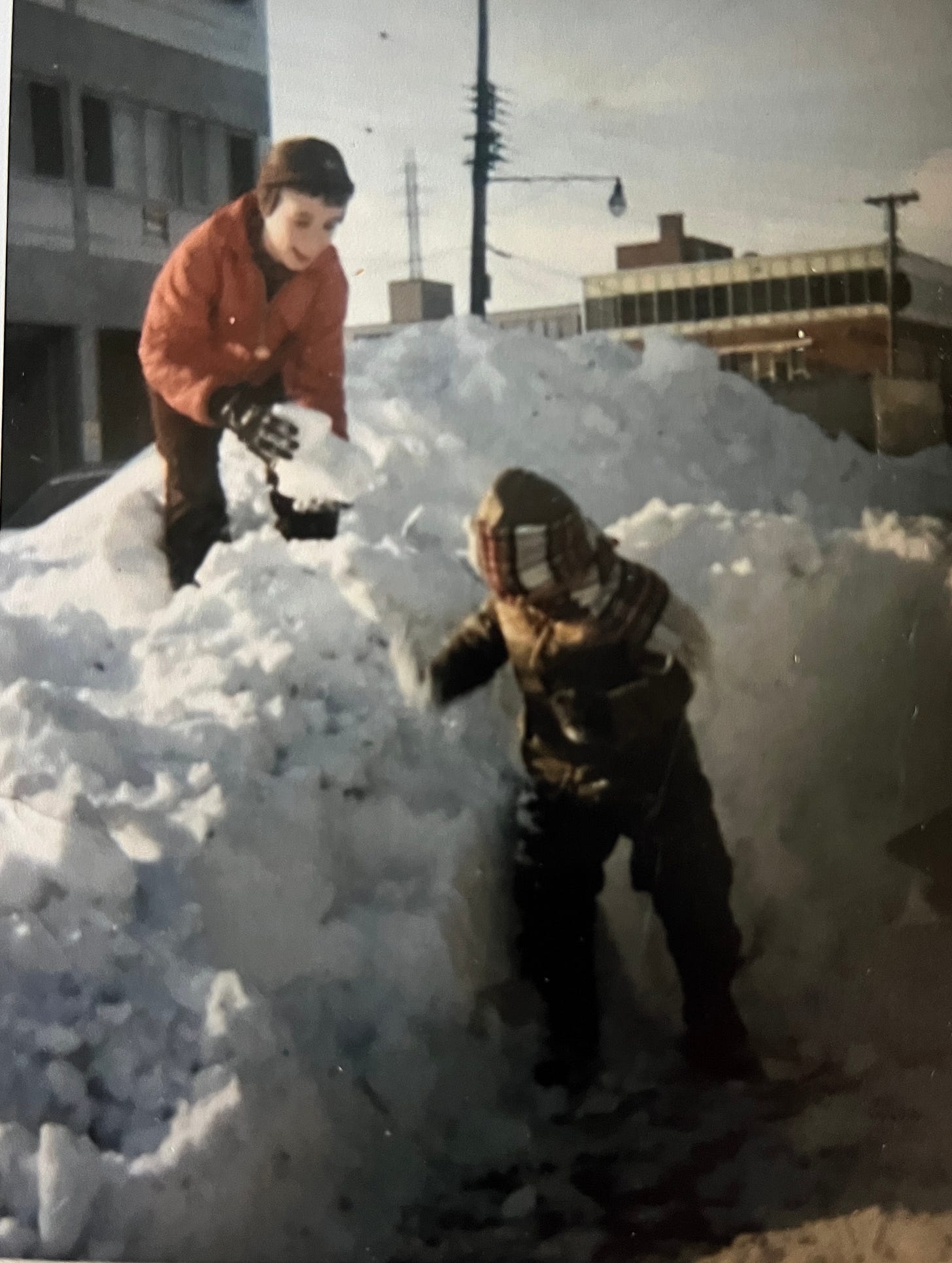

“Ma guarda come nevica!” Mom exclaimed to Pompeo and me as we sat in front of our black-and-white TV, trying to make sense of a Tom and Jerry cartoon.

We rushed to the window to witness the snowfall. A cold breeze slipped through the old wooden window frame on that late November afternoon.

By morning, so much snow had fallen that the bench near our front door had disappeared beneath it. I don’t remember if school was canceled or it was mom’s decision but I stayed home that day and I did not mind at all. Seeing all that snow was exciting, and skipping boring school gave me a quiet thrill of freedom.

School Challenges

At la récréation (recess), I would stand along the metal fence of the schoolyard, freezing, as the other kids played ballon chasseur.

Sometimes I talked to Remo, a red-haired, introverted boy. What drew me to him was that he spoke Italian and was as shy as I was. I believe he was the only other Italian kid in the French school.

“Remo, ma il freddo quant’è che finisce?”

When will the cold end? I’d ask.

He shrugged. “Ma non lo so! A Pasqua!”

I don’t know! Maybe by Easter!

I liked recess because it gave me a break from the classroom boredom, but I was always glad to go back inside. I hated the cold and felt too shy to join the games.

At lunch, skirmishes often broke out between boys from the French St-Simon school and the English-speaking John Cabot next door. Ironically, most of the John Cabot students were Italian immigrants like me, while St-Simon was mostly French-Québécois.

My Aunt Peppinella’s decision to enroll me in a bilingual school might have made sense for someone who already spoke the languages. But no one considered how difficult, how mentally exhausting, it would be for a newly arrived boy to learn two foreign languages in a world that felt completely alien.

So, each group would stand on its side of the fence, hurling insults.

“Awaiee! Mon espèce de wop!”

“Come on, you Wop!” yelled Robert at me from our side of St-Simon.

“Viens te battre! On va leur montrer à ces asti de spaghettis qu’ils ne sont pas les bienvenus chez nous!”

“Come fight, we’ll show these damn spaghetti noodles they’re not welcome here!” he shouted.

I slowly withdrew from the crowd, only to be taunted from the other side:

“Traitor! Traitor! You’re a traitor!” the John Cabot crowd pointing fingers at me.

Redefining Who I Was

In class, I stared at my copybook, half the page still blank. Mme Martineau paced the aisles, checking our work. When she reached my desk, she paused and frowned at my handwriting.

My letters were round and loose, the way I had learned back in Italy.

She didn’t say much, just asked me to come up. Then she handed me a new copybook, tight, lined pages, and a sheet filled with neat, angular sentences in her sharp handwriting. I was told to copy them exactly.

I had to stop writing the way I knew. No more wide loops or slanted letters. I was told to hold the pencil differently. Press harder. Write slower.

Each time I slipped into my old habits, she shook her head or crossed it out.

So, I began to copy. I erased over and over. Stayed in during recess to rewrite pages. After a while, I couldn’t remember what my own handwriting looked like. My writing became something foreign, no longer Italian, not yet Canadian.

And that was just the beginning. First the letters, then the words. Then how I spoke, stood, smiled.

I started watching people closely, how they answered questions, raised their hands, when they laughed. I began copying what seemed “right.” I stopped doing what felt natural and started doing what others might accept.

My life was being rewritten, one small correction at a time.

My First Love

Walking home from school with Danielle became a moment of peace and excitement. She had deep blue eyes and long, wavy hair.

Even with my limited vocabulary, I felt she understood me. I sensed she liked me, I certainly liked her.

But Patrick, the class’s brightest student, constantly pursued her, fuelling my jealousy.

One day, as we walked down Beauharnois Street, she said,

“Quelle est belle la fleur.”

How beautiful the flower is.

Patrick replied,

“C’est dommage qu’elle soit de l’autre côté de la clôture.”

Too bad it’s on the other side of the fence.

This was my moment. I dropped my schoolbag, vaulted over the fence, plucked the flower by its root, and handed it to Danielle before returning to the sidewalk.

She smiled. It was the most beautiful smile I had seen since arriving in Montreal.

I would walk her home on Jeanne Mance street almost every day. Up the few steps to the dark blue door, then wave goodbye, walking home with a smile.

What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Stronger (or so it’s said)

After what felt like an eternity, warm weather finally arrived. We had survived our first Canadian winter. School ended, and on the very last day, I learned I had failed fourth grade.

Mme Martineau spoke slowly in French:

“Agostino, tu es un enfant beaucoup plus avancé intellectuellement que les autres élèves de la classe. Ceci dit, je ne peux pas te donner un bulletin avec des notes. Je pense qu’il serait plus bénéfique pour toi de répéter l’année pour mieux assimiler la langue.”

Apparently, I was more advanced intellectually than the other students, but she could not give me a proper scored report card. She suggested repeating the year to better grasp the language.

All I understood was: I had failed. I would have to do it all over again.

I walked home heavy-hearted. Climbing the stairs to our second-floor flat, I found Mom in the kitchen.

Sitting at the table, I said, “Ho avuto la pagella oggi.”

(I got the report card today.)

She turned. “Allora, che dice?”

(So, what does it say?)

I hesitated.

“Dai, che hai? Mi sembri triste!”

(Come on, what’s wrong? You look sad!)

“Mamma, io non voglio più andare alla scuola bilingua. Non mi piace.”

(Mom, I don’t want to go to bilingual school anymore. I don’t like it.)

“Che si fatt?” she asked in our San Vittorese dialect.

(What’s wrong?)

I told her the teacher said I was smart but recommended repeating the year to better understand the language.

Then I went to my room, buried my head in the pillow, and prayed, prayed for something, anything, to happen so we could return to San Vittore. I couldn’t stand the thought of doing fourth grade again.

Even clinging to Mme Martineau’s words, “You are smarter and more advanced than the others”, didn’t ease my shame.

I felt cheated. Abandoned. Insecure.

All I could think of was Pino and Marco starting la scuola media in September, middle school. And I’d still be here, rewriting the same lines, in a language I didn’t yet own.

You can read all the essays and books about Italian migration, with data and figures—but nothing compares to a true story to immerse yourself in the everyday challenges it brings.

Because migration isn’t made of statistics and numbers, but of women, men, and children who must relearn how to live, often through struggle.

Thank you, Tino, for sharing your story.

De plus Mme Martineau, aurait dû te donner un diplôme pour avoir passé avec succès ta première année à Montréal après avoir émigré d’Italie.